Original Article

VOLUME: 39 | ISSUE: 4 | Dec 25, 2023 | PAGE: (178 - 182) | DOI: 10.24911/BioMedica/5-675

Comparative IgG Antibody Titers Following Second Dose of Sinopharm and Pfizer Vaccination

Authors: Hira Tanveer , Sehrish Zaffar , Muhammad Osama , Isma Ishaq , Javaria Arshad Malik , Rabiea Bilal , Afnan Talat , Aisha Talat

Article Info

Authors

Hira Tanveer

Demonstrator, Department of Pharmacology, CMH Lahore Medical College and Institute of Dentistry, Lahore (NUMS), Pakistan.

Sehrish Zaffar

Associate Professor, Department of Pharmacology, CMH Lahore Medical College and Institute of Dentistry, Lahore (NUMS), Pakistan.

Muhammad Osama

Demonstrator, Department of Pharmacology, CMH Lahore Medical College and Institute of Dentistry, Lahore (NUMS), Pakistan.

Isma Ishaq

Demonstrator, Department of Pharmacology, CMH Lahore MC and Institute of Dentistry, Lahore,(NUMS), Islamabad, Paksitan.

Javaria Arshad Malik

Associate Professor, Department of Pharmacology, CMH Lahore Medical College and Institute of Dentistry, Lahore. NUMS, Pakistan.

Rabiea Bilal

Professor, Department of Pharmacology, CMH Lahore Medical College and Institute of Dentistry, Lahore, Pakistan.

Afnan Talat

Demonstrator, Department of Pharmacology, CMH Lahore Medical College and Institute of Dentistry, Lahore, Pakistan.

Aisha Talat

Professor, Department of Pharmacology, Continental Medical College, Lahore, Pakistan.

Publication History

Received: September 28, 2023

Revised: November 22, 2023

Accepted: December 17, 2023

Published: December 25, 2023

Abstract

Background and Objective: The vaccines Sinopharm and Pfizer account for more than 7.3 billion vaccinations across the globe. Study data shows that the protection offered by these vaccines wanes with time, which is why the third dose of a different or same vaccine may become necessary. The objective of this study was to compare the levels of IgG in the post-vaccination phase, with two different vaccines, Sinopharm and Pfizer.

Methodology: A cross sectional study was conducted at CMH Lahore Medical College and Institute of Dentistry, after approval by the Ethical committee. A total of 100 participants, who were completely vaccinated, with either Sinopharm or Pfizer, at least six weeks before, were included in the study. Participants with concurrent infection, incomplete vaccination or any known disease, were excluded from the study. Written consent was obtained from all the participants. A predesigned questionnaire, adapted from similar studies, was used for data collection. Afterwards, blood samples were collected and IgG antibody levels were estimated using RD-RatioDiagnostics SARS-COV-2 virus IgG ELISA kit (E-COG-K105). The collected data was analyzed with SPSS software. Results with p value < 0.05 were taken as significant.

Results: Mean age of the participants was 20.18±1.29 years. Mean antibody titers, six weeks post-vaccination, were 5453.73±609.15 U/ml and 10786.86±1525.49 U/ml in Sinopharm and Pfizer groups, respectively. The difference was statistically significant (p=0.0004).

Conclusion: Antibody response is considerably higher in Pfizer-vaccinated individuals, in comparison to Sinopharm.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Pfizer, Sinopharm, mRNA vaccines, COVID-19 vaccines, COVID-19 serological testing

Pubmed Style

Hira Tanveer, Sehrish Zaffar, Muhammad Osama, Isma Ishaq, Javaria Arshad Malik, Rabiea Bilal, Afnan Talat, Aisha Talat. Comparative IgG Antibody Titers Following Second Dose of Sinopharm and Pfizer Vaccination. BioMedica. 2023; 25 (December 2023): 178-182. doi:10.24911/BioMedica/5-675

Web Style

Hira Tanveer, Sehrish Zaffar, Muhammad Osama, Isma Ishaq, Javaria Arshad Malik, Rabiea Bilal, Afnan Talat, Aisha Talat. Comparative IgG Antibody Titers Following Second Dose of Sinopharm and Pfizer Vaccination. https://biomedicapk.com/articles/online_first/675 [Access: July 27, 2024]. doi:10.24911/BioMedica/5-675

AMA (American Medical Association) Style

Hira Tanveer, Sehrish Zaffar, Muhammad Osama, Isma Ishaq, Javaria Arshad Malik, Rabiea Bilal, Afnan Talat, Aisha Talat. Comparative IgG Antibody Titers Following Second Dose of Sinopharm and Pfizer Vaccination. BioMedica. 2023; 25 (December 2023): 178-182. doi:10.24911/BioMedica/5-675

Vancouver/ICMJE Style

Hira Tanveer, Sehrish Zaffar, Muhammad Osama, Isma Ishaq, Javaria Arshad Malik, Rabiea Bilal, Afnan Talat, Aisha Talat. Comparative IgG Antibody Titers Following Second Dose of Sinopharm and Pfizer Vaccination. BioMedica. (2023), [cited July 27, 2024]; 25 (December 2023): 178-182. doi:10.24911/BioMedica/5-675

Harvard Style

Hira Tanveer, Sehrish Zaffar, Muhammad Osama, Isma Ishaq, Javaria Arshad Malik, Rabiea Bilal, Afnan Talat, Aisha Talat (2023) Comparative IgG Antibody Titers Following Second Dose of Sinopharm and Pfizer Vaccination. BioMedica, 25 (December 2023): 178-182. doi:10.24911/BioMedica/5-675

Chicago Style

Hira Tanveer, Sehrish Zaffar, Muhammad Osama, Isma Ishaq, Javaria Arshad Malik, Rabiea Bilal, Afnan Talat, Aisha Talat. "Comparative IgG Antibody Titers Following Second Dose of Sinopharm and Pfizer Vaccination." 25 (2023), 178-182. doi:10.24911/BioMedica/5-675

MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style

Hira Tanveer, Sehrish Zaffar, Muhammad Osama, Isma Ishaq, Javaria Arshad Malik, Rabiea Bilal, Afnan Talat, Aisha Talat. "Comparative IgG Antibody Titers Following Second Dose of Sinopharm and Pfizer Vaccination." 25.December 2023 (2023), 178-182. Print. doi:10.24911/BioMedica/5-675

APA (American Psychological Association) Style

Hira Tanveer, Sehrish Zaffar, Muhammad Osama, Isma Ishaq, Javaria Arshad Malik, Rabiea Bilal, Afnan Talat, Aisha Talat (2023) Comparative IgG Antibody Titers Following Second Dose of Sinopharm and Pfizer Vaccination. , 25 (December 2023), 178-182. doi:10.24911/BioMedica/5-675

Biomedica - Official Journal of University of Health Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan

Volume 39(4):178-182

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Comparative IgG antibody titers following second dose of Sinopharm and Pfizer vaccination

Hira Tanveer1, Sehrish Zaffar2, Muhammad Osama1, Isma Ishaq1, Javaria Arshad Malik2, Rabiea Bilal3,4, Afnan Talat1, Aisha Talat5

Received: 28 September 2023 Revised date: 22 November 2023 Accepted: 17 December 2023

Correspondence to: Sehrish Zaffar

*Associate Professor, Department of Pharmacology, Combined Military Hospital Lahore Medical College and Institute of Dentistry, Lahore, Pakistan.

Email: sehrish.zaffar@gmail.com

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

ABSTRACT

Background and Objective:

The SARS-CoV-2 vaccines of Sinopharm and Pfizer have been reported to vaccinate more than 7.3 billion people across the globe. However, the protection offered by these mRNA vaccines wanes with time, which is why the third dose of a different or same vaccine may become necessary. The objective of this study was to compare the levels of immunoglobulin G (IgG) in the post-vaccination phase in the local population after two doses with Sinopharm and Pfizer vaccination.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted at the Combined Military Hospital (CMH) Medical College and Institute of Dentistry, Lahore, Pakistan. A total of 100 adult participants who were completely vaccinated with either Sinopharm or Pfizer, at least 6 weeks before, were included in the study after taking informed consent. Blood samples were collected and SARS-COV-2 virus IgG antibody levels were estimated using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The collected data were analyzed while taking a p value < 0.05 as significant.

Results:

The mean age of the participants was 20.18 ± 1.29 years. Mean antibody titers, six weeks post-vaccination were 5453.73 ± 609.15 units per milliliter (U/ml) and 10786.86 ± 1525.49 U/ml in Sinopharm and Pfizer groups, respectively. The difference was statistically significant (p = 0.0004).

Conclusion:

Antibody response was considerably higher in Pfizer-vaccinated individuals in comparison to Sinopharm in the local population from Pakistan.

Keywords:

SARS-CoV-2, Pfizer, Sinopharm, mRNA vaccines, COVID-19 vaccines, ELISA.

Introduction

The severe-acute-respiratory-syndrome-related coronavirus (SARS-COV) has inflicted havoc on the immunologically naïve population, globally. This variant of coronavirus originated in the wet market of the Wuhan region of China in late 2019, and in March 2020, after 180 million confirmed cases and 3.8 million deaths, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared coronavirus a pandemic.1

The virus impacted the respiratory system with early symptoms similar to influenza infection, later morphing into respiratory failure through cytokine storm and atypical pneumonia or resolving completely on its own. The management of the acute respiratory syndrome secondary to coronavirus, in clinical settings, was symptomatic alone.2

To combat the spread of the virus and subsequent disease, the WHO declared vaccination and herd immunity as promising options. Herd immunity occurs when the majority of the population is immune to the virus either through natural infection or vaccination.1 The immunity induced through natural infection and vaccination curtails disease spread, and offers a modicum of protection against serious disease and reinfection.3

Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus

and Severe-acute-respiratory-syndrome-related coronavirus (SARS-CoV-1) paved the way for the development of vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 because of the analogous target protein - the surface spike protein. The vaccine development against SARS-CoV-2 started in January 2020, as soon as the genetic sequence of the virus became available. The immunogen used in these vaccines is either the viral spike protein or the ancestral (Wuhan-like) virus.4 Antibodies against these spike proteins, particularly the receptor-binding domain, prevent the attachment of the viral body to the host and neutralize the virus.5 Even though the antibody response to the spike protein shows variability, it is not unlike the typical antibody response as seen with a respiratory virus, with an initial boost of plasma blast-derived antibodies, followed by a dip, and then a baseline level that is maintained by the long-lasting plasma cells.6

Studies show the effectiveness of these vaccines between 50% and 95%, and this protection against re-infection rises to 89% in case of natural infection.7,8 Serological assays from convalescent and vaccinated populations indicate that the immunity is derived from SARS-CoV-2 specific CD-4+ and CD-8+ T-cells, and the level of these circulating antibodies wanes with time, providing only temporary protective immunity.9

In humans who have undergone natural infection with COVID-19, there is mucosal antibody response as well. Research shows that the primary cells targeting the spike proteins are the CD4+ T-cells, with fewer CD8+ T-cells being involved in this immune process.10 The vaccines against COVID-19 that are administered intradermally or intramuscularly induce mainly systemic IgG antibodies, with no secretory IgA response, unlike the natural infection, which also induces IgA.11 Thus, it can be established that the vaccines developed to date, have a role in disease attenuation rather than giving sterilizing immunity.

With the evolving strain, there are reports of breakthrough infections, as well as clinical trials, suggesting the ineffectiveness of the current vaccines against some of the prevalent variants.12 There is growing concern regarding the evolution and variation of SARS-CoV-2 that contains mutations in the spike gene, which in turn could impair the efficacy of current vaccines and monoclonal antibody therapies.13 Another concerning element is the reduced protection offered by the waning antibody titers over time.14

Understanding the relationship between antibody titers and protection against coronavirus is crucial for developing effective strategies for antiviral treatment, vaccines, and epidemiological control. By studying the correlation between antibody titers and protection against coronavirus, researchers can determine the level of immunity conferred by antibodies and their effectiveness in preventing reinfection.15 This study was therefore designed to compare the levels of IgG in the post-vaccination phase in the local population, with the two most commonly administered vaccines, Sinopharm and Pfizer.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted at CMH Lahore Medical College and Institute of Dentistry, (CMH LMC & IOD), Pakistan, from March 2022 to September 2022. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Review Committee of CMH LMC & IOD, before the commencement of the study. A sample size of 100 participants using Openepi software was calculated.16,17 Nonprobability convenience sampling was done. Fifty participants, within the age group of 18-25 years, who have received vaccination according to the recommended vaccination schedule (21-28 days between first and second dose, with either Sinopharm or Pfizer) at least six weeks before, were included in each group. Participants with concurrent infection, incomplete vaccination, or any known chronic disease, were excluded from the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Respondents were assured with regard to the confidentiality of the data. A brief predesigned questionnaire was adapted,18,19 validated, and used for data collection. Participants were asked about demographic details, type of vaccine administered, development of post-vaccination COVID-19 infection, and intentions for booster dose.

To collect blood for the estimation of antibody titers, the complete aseptic technique was adopted by skilled laboratory personnel. The blood samples were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm at room temperature, for five minutes. The serum was collected and stored at −20°C until further analysis. IgG antibody levels were estimated using RD-RatioDiagnostics SARS-COV-2 virus IgG ELISA kit (Catalogue# E-COG-K105). The procedure was carried out strictly according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical Analysis

The data collected were analyzed using statistical package for social sciences version 25. Descriptive statistics were presented as mean ± SD for quantitative variables, e.g., age and IgG antibody level, while frequency and percentages were used for qualitative variables, e.g., COVID infection after the first dose and intention to receive booster dose. Independent t-test and Chi-square test were applied for comparison of group means and frequencies, respectively. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 100 participants were included in the study, out of which 58 were females and 42 were males. The mean age of the participants was 20.18 ± 1.29 years. Following the first dose of vaccination with Sinopharm and Pfizer, 13% and 8% of participants developed symptomatic COVID-19 infection. A total of 59 participants (59%) intended to get the booster dose in the following months (Table 1).

Table 1. Frequency of COVID-19 infection and response to booster doses in participants (n = 100).

| Survey questionnaire response | Vaccine | Total | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SinoPharm | Pfizer | |||||

| COVID-19 infection after first dose | Yes | Count | 13 | 8 | 21 | 0.220 |

| % of total | 13.0% | 8.0% | 21.0% | |||

| No | Count | 37 | 42 | 79 | ||

| % of total | 37.0% | 42.0% | 79.0% | |||

| Total | Count | 50 | 50 | 100 | ||

| % of total | 50.0% | 50.0% | 100.0% | |||

| Intention to receive booster dose | Yes | Count | 36 | 23 | 59 | 0.008 |

| % of total | 36.0% | 23.0% | 59.0% | |||

| No | Count | 14 | 27 | 41 | ||

| % of total | 14.0% | 27.0% | 41.0% | |||

| Total | Count | 50 | 50 | 100 | ||

| % of total | 50.0% | 50.0% | 100.0% | |||

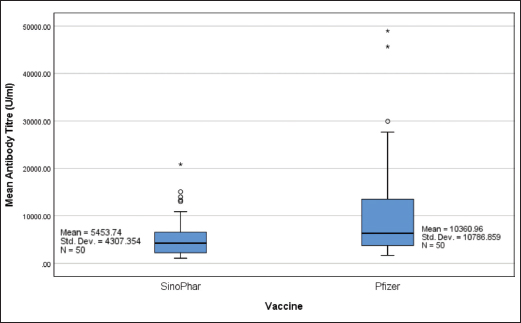

Figure 1. Mean antibody titers (U/ml) following two doses of Sinopharm and Pfizer (n = 50 each).

Mean antibody titers, six weeks post-vaccination, were 5453.73 ± 609.15 and 10786.86 ± 1525.49 U/ml in Sinopharm and Pfizer groups, respectively (Figure 1). The difference was statistically significant (p = 0.004).

Discussion

COVID-19 has changed the global perspective of medicine altogether, since the start of the pandemic. The emergence of new variants has necessitated the development of long-term immunity against the virus.11 This study was designed to compare the antibody (IgG) response of two most commonly administered vaccines in Pakistan; Sinopharm and Pfizer after two complete doses. A statistically significant difference was found between the mean antibody levels with Sinopharm and Pfizer (p = 0.004). In contrast, a recent Jordanian study reported significantly raised antibody titers, post-vaccination, with Pfizer-BioNTech in comparison to Sinopharm (p < 0.001). Among recipients of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccination, 140 (99.3%) subjects had positive IgG titers whereas 126 (85.7%) of those who received the Sinopharm vaccine had positive IgG (p < 0.001). Pfizer-BioNTech recipients had a mean IgG titer of 515.5 ± 1143.5 binding antibody units per milliliter (BAU/ml) while Sinopharm participants had a mean titer of 170.0 ± 230.0 BAU/ml (p < 0.001).20 Another study by the working group of Austria and Japan observed the antibody response following a messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) (Novavax), a protein-based (Pfizer-BioNTech), and a vector-based (AstraZeneca) vaccine. Average post-vaccination anti-SARS-CoV-2 potency in international units per milliliter (IU/ml) was 548, 557, and 202 for recipients of Novavax, Pfizer-BioNTech, and AstraZeneca, respectively. Neutralizing antibody levels were equivalent for the Pfizer-BioNTech and Novavax, but significantly lower in the AstraZeneca group (p = 0.004).21 A study conducted in Iraq documented that IgG antibodies were considerably increased in 97% of patients who received the Pfizer vaccine 30 days following the second dose when compared to 92% of patients who received the AstraZeneca vaccine and 60% of patients who received the Sinopharm vaccine.17

Alarmingly, multiple studies have documented insufficient immune response, following Sinovac vaccination.22,23

At this point, it is evident that mRNA vaccines, such as Pfizer-BioNTech, have much higher efficacy as compared to the inactivated-virus-based vaccines, such as Sinopharm. Nevertheless, the time at which Sinopharm was developed, was a crisis in itself. The COVID-19 outbreak was at its peak. The mRNA vaccines required time for the development and maintenance of the cold chain, which totally justifies the widespread use of Sinopharm in Pakistan. However, the fading antibody responses with these vaccines warrant the need for booster doses24, preferably with much more efficacious mRNA vaccines. Moreover, currently, Pfizer-BioNTech is abundantly available in Pakistan; therefore, booster doses may be chosen by physicians or the public at large on the basis of the best available evidence.

Conclusion

The post-vaccination IgG antibody titer after two doses of the Pfizer vaccine was significantly higher than the Sinopharm in the local population.

Limitations of the Study

This study had a few limitations. First, it was a self-funded work, so limited resources did not allow a bigger sample size. Second, it was a cross-sectional study that measured the antibody levels only once, in a specific time period, post-vaccination. Hence, this study cannot predict waning antibody response. We highly recommend further, more extensive studies to estimate the antibody responses against Sinopharm and Pfizer over a longer duration, since they have been used to vaccinate the majority of the population in Pakistan.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Abdul Mateen and Dr. Rameez Ahmed from the Pharmacology Department of CMH Lahore Medical College, Lahore, Pakistan, for their assistance in data collection.

List of Abbreviations

| BAU/ml | Binding antibody units per milliliter |

| SARS-CoV | Severe-acute-respiratory-syndrome-related coronavirus |

| U/ml | Units per milliliter |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Conflict of interest

The authors declare to have no direct or indirect conflicting interest with the vaccination companies mentioned in the manuscript.

Grant support and financial disclosure

None to disclose.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of CMH Lahore Medical College and Institute of Dentistry, Lahore, Pakistan, on 05 Jan 2022 vide Letter No. 659/ERC/CMH/LMC.

Authors’ contributions

HT: Conception and design of study.

SZ and JAM: Drafting of manuscript and data interpretation.

MO and II: Drafting of manuscript, acquisition, and analysis of data.

RB and AT: Critical intellectual input and supervision of work.

ALL AUTHORS: Approval of the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Authors’ Details

Hira Tanveer1, Sehrish Zaffar2, Muhammad Osama1, Isma Ishaq1, Javaria Arshad Malik2, Rabiea Bilal3,4, Afnan Talat1, Aisha Talat5

- Demonstrator, Department of Pharmacology, Combined Military Hospital Lahore Medical College and Institute of Dentistry, Lahore. National University of Medical Sciences, Islamabad, Pakistan.

- Associate Professor, Department of Pharmacology, Combined Military Hospital Lahore Medical College and Institute of Dentistry, Lahore. National University of Medical Sciences, Islamabad, Pakistan.

- Professor, Department of Pharmacology, Combined Military Hospital Lahore Medical College and Institute of Dentistry, Lahore, Pakistan.

- National University of Medical Sciences, Islamabad, Pakistan.

- Professor, Department of Pharmacology, Continental Medical College, Lahore, Pakistan.

References

- Mishra SK, Pradhan SK, Pati S, Sahu S, Nanda RK. Waning of anti-spike antibodies in AZD1222 (ChAdOx1) vaccinated healthcare providers: a prospective longitudinal study. Cureus. 2021;13(11):e19879. https://doi.org/10.7759/CUREUS.19879

- Hamady A, Lee JJ, Loboda ZA. Waning antibody responses in COVID-19: What can we learn from the analysis of other coronaviruses? Infection. 2022;50(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1007/S15010-021-01664-Z

- Franchi M, Pellegrini G, Cereda D, Bortolan F, Leoni O, Pavesi G, et al. Natural and vaccine-induced immunity are equivalent for the protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Infect Public Health. 2023;16(8):1137–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JIPH.2023.05.018

- Cromer D, Steain M, Reynaldi A, Schlub TE, Wheatley AK, Juno JA, et al. Neutralising antibody titers as predictors of protection against SARS-CoV-2 variants and the impact of boosting: a meta-analysis. Lancet Microbe. 2022;3(1):e52–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00267-6

- Krammer F. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in development. Nature. 2020;586(7830):516–27. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2798-3

- Wajnberg A, Amanat F, Firpo A, Altman DR, Bailey MJ, Mansour M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection induces robust, neutralizing antibody responses that are stable for at least three months. MedRxiv. 2020;2020–07. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.14.20151126

- Khoury DS, Cromer D, Reynaldi A, Schlub TE, Wheatley AK, Juno JA, et al. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27(7):1205–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01377-8

- Feikin DR, Higdon MM, Abu-Raddad LJ, Andrews N, Araos R, Goldberg Y, et al. Duration of effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 disease: results of a systematic review and meta-regression. Lancet. 2022;399(10328):924–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00152-0

- Muecksch F, Wise H, Batchelor B, Squires M, Semple E, Richardson C, et al. Longitudinal serological analysis and neutralizing antibody levels in coronavirus disease 2019 convalescent patients. J Infect Dis. 2021;223(3):389–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa659

- Galipeau Y, Greig M, Liu G, Driedger M, Langlois MA. Humoral responses and serological assays in SARS-CoV-2 infections. Front Immunol. 2020;11:610688. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.610688

- Su F, Patel GB, Hu S, Chen W. Induction of mucosal immunity through systemic immunization: Phantom or reality? Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(4):1070–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2015.1114195

- Madhi SA, Baillie V, Cutland CL, Voysey M, Koen AL, Fairlie L, et al. Efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 COVID-19 vaccine against the B. 1.351 variant. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(20):1885–98. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2102214

- Wang P, Nair MS, Liu L, Iketani S, Luo Y, Guo Y, et al. Antibody resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants B. 1.351 and B. 1.1.7. Nature. 2021;593(7857):130–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03398-2

- Thomas SJ, Moreira Jr ED, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine through 6 months. N Engl J Med. 202;385(19):1761–73. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2110345

- Feng S, Phillips DJ, White T, Sayal H, Aley PK, Bibi S, et al. Correlates of protection against symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27(11):2032–40. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01540-1IF: 82.9 Q1

- Al-Khazrajy DF, Raddam QN. Evaluation of the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines (Pfizer, Astra Zeneca, Sinopharm) using Iraqi local samples. Neuroquantology. 2022;20(4):73–81. https://doi.org/10.14704/nq.2022.20.4.NQ22097

- Majed SO. Comparison of antibody levels produced by Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Sinopharm vaccination in COVID-19 patients in Erbil City-Iraq. Cell Mol Biol. 2023;69(3):103–12. https://doi.org/10.14715/cmb/2023.69.3.14

- Jeong S, Lee N, Lee SK, Cho EJ, Hyun J, Park MJ, et al. Comparison of the results of five SARS-CoV-2 antibody assays before and after the first and second ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccinations among health care workers: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Microbiol. 2021;59(12):e01788–21. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01788-21

- Kelliher MT, Levy JJ, Nerenz RD, Poore B, Johnston AA, Rogers AR, et al. Comparison of symptoms and antibody response following administration of Moderna or Pfizer SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Archi Pathol Lab Med. 2022;146(6):677–85. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2021-0607-SA

- Alqassieh R, Suleiman A, Abu-Halaweh S, Santarisi A, Shatnawi O, Shdaifat L, et al. Pfizer-BioNTech and Sinopharm: a comparative study on post-vaccination antibody titers. Vaccines. 2021;9(11):1223. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9111223

- Karbiener M, Farcet MR, Zollner A, Masuda T, Mori M, Moschen AR, et al. Calibrated comparison of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody levels in response to protein-, mRNA-, and vector-based COVID-19 vaccines. NPJ Vaccines. 2022;7(1):22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-022-00455-3

- Ata S, Cil T, Duman BB, Unal N. Evaluation of antibody response after two doses of the Sinovac vaccine and the potential need for booster doses in cancer patients. J Med Virol. 2022;94(6):2487–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/JMV.27665

- Muena NA, García-Salum T, Pardo-Roa C, Avendaño MJ, Serrano EF, Levican J, et al. Induction of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies by CoronaVac and BNT162b2 vaccines in naïve and previously infected individuals. EBioMed. 2022;78:103972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.103972

- Saeed U, Uppal SR, Piracha ZZ, Uppal R. SARS-CoV-2 spike antibody levels trend among Sinopharm vaccinated people. Iran J Public Health. 2021;50(7):1486–87. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v50i7.6640