Biomedica - Official Journal of University of Health Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan

Volume 38(3):149-156

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Stigma, perceived family support, and post-traumatic stress experienced by seropositive HIV patients in Pakistan

Kiran Zia1,2*, Faiza Khalid1,3

Received: 23 June 2022 Revised date: 22 August 2022 Accepted: 06 September 2022

Correspondence to: Gul Mehar Javaid Bukhari

*Lecturer, Department of Eastern Medicine, Qarshi University, Lahore, Pakistan.

Email: kiranzia3@yahoo.com

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

ABSTRACT

Background and Objective:

Stigmatization and discrimination are phenomena familiar to all human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients, which create a significant amount of stress; little is known about the role of family support in alleviation of this stressful condition. The current study aims to investigate the relationship between the perceptions of family support, stigmatization, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress in HIV-positive patients in Pakistan.

Methods:

A total of 100 seropositive patients, aged between 18 and 50 years, were approached through professional organizations in Lahore, Pakistan, based on purposive and snowball sampling strategies. The magnitude of stigma experienced by the patients was assessed by administering the Berger HIV stigma scale. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support and post-traumatic stress disorder checklist were used to assess post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) and perceived family support (PFS).

Results:

The study identified a positive relationship between experiencing stigma and the development of PTSS. Also, a significant inverse relationship between PFS and PTSS was observed, whereas a consequential negative association between experiencing stigma and PFS was evident in patients who disclosed their illness to their families.

Conclusion:

The current study documents that HIV seropositive patients in Pakistan experience high levels of stigma, especially in relation to the disease disclosure to their families and other social contacts. An already immune compromised status and stigmatization leads to significant stress symptoms which ultimately decrease the perception about accessibility of social support in the times of crisis.

Keywords:

Human immunodeficiency virus, seropositive, stigma, perceived family support, post-traumatic stress.

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is subject to incredible stigma. HIV is a virus, but stigma is not; however, stigma severely infects a person’s health, and social and personal life more than any other kind of virus.1 The lifelong disease, HIV, increased drastically in Pakistan to around 165,000 patients but only 15,370 cases were registered and 22,000 were newly infected by the disease. The result of survey concluded that Pakistan’s largest populated province, Punjab had the highest number of cases of HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), i.e., almost 60,000, whereas in Sindh it was 52,000, in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) it was 11,000, and many cases were reported in Balochistan.2 From January 2016 to June 2019, 24,331 additional cases of HIV/AIDS had been registered nationwide, 3,878 cases were from Punjab, 2,521 cases from Sindh, 881 and 291 new cases from KPK and Balochistan, respectively.3 According to the Punjab Health Department, certain cities of Punjab are most vulnerable and at risk of rapid HIV transmission including Lahore, Dera Ghazi Khan (DG Khan), Multan, Rawalpindi, Gujrat, Faisalabad, and Sargodha. In Pakistan, basic reasons for the drastic increase in cases are lack of substantial information and awareness about HIV and nondisclosure due to fear of stigmatization, rejection by loved ones, and discrimination within society.4

Pakistan is situated in South Central Asia with neighboring high-risk countries for HIV transmissions such as India, Afghanistan, and China. In 1987, the first case of HIV was diagnosed.5 The most common modes of the transmission of the life-threatening virus, HIV, in Pakistan are heterosexuality, unclean blood transfusion or blood products, injecting drug use, male-to-male or bisexual relationships, mother-to-child transmission, and transmission of undetermined origin.6

Various empirical evidence show that people living with HIV (PLWH) lack treatment compliance due to stigmatization involved as reflected by poor medical adherence.7 This may escalate the disease leading to gradual and progressive suppression of the human immune system and to the development of AIDS. AIDS is a lifelong disease that attacks the immune system CD4 (T cells) that fight against infections/viruses and reduces the amount of CD4+ cells making the body more vulnerable to other infections and cancers.8

Stigma is aberration from social expectation, divergence between social desire, expectation, and actual situation. Stigma is associated with functional limitations, chronic illnesses (cancer and HIV), and physical diseases. The patient often feels guilty and ashamed about the illness which often results in causing psychological disturbances.9 There are several empirical investigations that reflect upon the multidimensional nature of stigma associated with HIV. This stigma can be characterized as social stigma, self-stigma, and treatment system stigma.10 When a person experiences any illness, the stigma associated with it often leads to negative experiences like rejection, marginalization, and ultimately discrimination.11 The PLWH feel increased levels of stress which have an adverse effect on their health causing a further decrease in the CD4+ cells count.12

PLWH face psychological stress due to the stigma associated with the disease. Perceived family support (PFS) can play a vital role in amending and enhancing their well-being. It has a buffering effect on stress and promotes emotional well-being, whereas actual support is directly or indirectly related to the disclosure of HIV status.13 Social fear, rejection, and discrimination associated with the illness leads to stigmatization and often makes it difficult for them to talk about HIV with their family, doctors, and stakeholders.14 The disclosure of having HIV is thus a daunting task and many factors cause a hindrance in its course. Conversations entailing a confession of having HIV go through a difficult, selective, and systematic process because it is directly related to a decrease in support and increased levels of discrimination. One of the factors that impacts these conversations is the type of relationship one has to the person.15

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PSTD) is a serious and petrifying illness that develops when an individual witnesses a terrifying event or any substantial trauma. According to Zhang et al.16, males and females with HIV encounter many stressful events, among which revealing their illness is the most stressful one. Disclosure of HIV arises other stressors including sexual assault/abuse, marital violence, and even separation or divorce. Many women with HIV are victimized by society resulting in the escalation of stress levels which affect their health or result in HIV progression. Studies reveal that health impairment due to HIV is more likely to cause psychological symptoms of depression and PTSD in the patients.17 HIV stigma is a potential stressor for PLWH. Vanable et al.18 found the relationship between experiencing stigma, depression, medication adherence, HIV disclosure, and sexual risk among HIV-positive men and women as these experiences are associated with psychological adjustments.

With Pakistan being among the countries that are in the transition phase, there is an alarmingly high risk of the spread of HIV. The country shares its border with India and Afghanistan and there are frequent opportunities of people travelling in these countries. Furthermore, the high rates of poverty and illiteracy, no proper check and balance on contaminated blood transfusions, and disposal of used syringes and injections, lack of awareness about sexual safe practices, and lesser use of contraceptives lead to higher probability of spread of sexually transmitted diseases especially in rural areas.19

On the contrary, scant research is published in Pakistan to elaborate this issue. The current study aims to identify the role and potential link between stigma experienced by the HIV patients, PFS, and post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) with or without disclosure of the disease.

Methods

This cross-sectional, descriptive study was conducted on 100 HIV-positive patients recruited through the snowball sampling strategy from Services hospital, Lahore, with the permission of Punjab AIDS Control Program (PACP), a project of Secondary Health Department of Punjab, Pakistan, and from different nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). The study was conducted from November 2021 to April 2022.

Inclusion criteria were HIV-positive male, female, and transgender patients aged between 18 and 50 years with an average time of 6–12 months since diagnosis. Exclusion criteria were patients with debilitated health conditions and/or who were not comfortable in response sharing.

The Berger HIV stigma scale (HSS), the multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MPSS), and post-traumatic stress disorder checklist (PCL-5) were applied in the proforma and permission was taken from respective authors. During the data collection process, all relevant ethical considerations were undertaken, and every patient was counseled during the questionnaire-filling process. To approach the transgender community, permission was taken from a local NGO. Patients were debriefed about the research purpose, and to ensure their willingness to contribute to current research, an informed written consent was taken from each participant. Participants were informed about the purpose of research; confidentiality and privacy of information were maintained during the research.

Demographic information like age, gender, education, religion, marital status, family system, city, source of transmission, and disclosure of illness were recorded.

Berger HIV stigma scale

This scale comprises two sets of items; the first set has 23 items and second set has 17 items. The first set measures social and emotional aspects of having HIV, whereas in the second set of items a person must imagine if she/he did not disclose having HIV. The tool covered four domains related to stigma that were “internalize stigma subscale, disclosure concern subscale, negative self-image subscale, and public attitude subscale.” Each question was to be answered on a 4-point Likert scale where 1 represents strongly disagree and 4 represents strongly agree. Item numbers 8 and 21 were reverse scored as suggested by the original author.20

The multidimensional scale of perceived social support

Zimet et al.21 developed the MPSS which intended to measure the perception of social support or availability of support when it will be needed. This scale was translated by Jibeen and Khalid 22 into the native language (Urdu). MPSS consists of 12 items related to 3 domains: family subscale, friends subscale, and significant other subscale. Each dimension is assessed with four items. It is 7-point Likert scale (with 1 = very strongly disagree and 7 = very strongly agree).

Post-traumatic stress disorder checklist

The PCL-5 scale was developed by Weathers et al.23. It is used for multiple purposes, including checking the effectiveness of treatment, pre and post-testing of PTSD symptoms, screening of PTSD, and making provisional PTSD diagnosis. It consists of 20 items that are based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) devised by the American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 criteria of PSTD, such as disturbing, repeated unwanted memories or dreams related to traumatic event, reliving of traumatic event in imagination, feeling upset, avoiding places and person’s that are reminders of the experience, selective amnesia, strong negative thinking, blaming oneself or others for the experience, loss of interest, concentration problems, and insomnia. The PCL scale’s item are scored on a 5-point Likert scale (with 0 = not at all and 4 = extremely). All items were designed according to DSM-5 criteria for PTSD.

All selected tools were in the native language (Urdu) and proper instructions were provided to all the patients. For some participants, items of questionnaires were read out when they felt uncomfortable or if they had any query while reading it. In the end, the patients were regarded for being part of the research and counseled.

Results

In the current study, three tools and demographic sheets were used for collecting biographic, personal information, and responses of patients. The demographic peculiarity of the data showed that majority of the patients were aged between 27 and 36 years (n = 40, 40%). There were 60 males, 33 females, and 7 transgenders; 26% of the patients were illiterate, whereas 74% were educated (from primary schooling to Master’s degree). All the participants were Muslims. Regarding areas of residence, 51% of the patients belonged to Lahore, 9% from DG Khan, 5% from Sialkot, 8% from Mianwali, and 6% from Gujranwala.

The data included 59 married patients, while 25 were single; 5 were widowed and 11 had divorced. Furthermore, 43% of the patients belong to a nuclear family system and 57% lived in a joint family system. Less than half of the patients (47%) disclosed about their illness to their family and other close social contacts, whereas 53% had hidden their seropositive status.

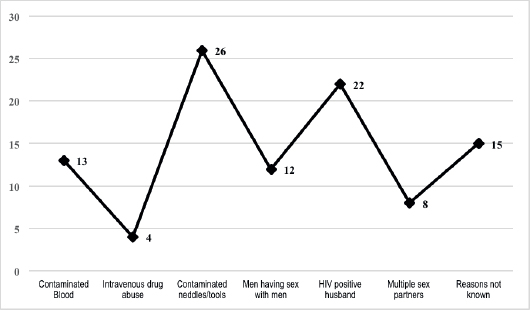

The main modes of HIV transmission in this population were through contaminated needles/blades and dental tools, followed by sexual contact with HIV-positive husbands, while 15% of the patients were unsure of their route of transmission (Figure 1).

It was found that those who had disclosed their seropositivity to family and friends or significant closer ones, experienced more stigma and lesser perception of family support as compared to the patients who did not disclose. This mean difference was calculated by computing independent sample t-test (Table 1) that showed a significant (p < 0.05) mean difference between the patients with and without disclosure. The value of Cohen’s d indicated a medium effect size.

The participants who did not disclose their illness (M = 4.42, SD = 1.46) had a higher PFS as compared to the ones who had disclosed their illness (M = 3.77, SD = 1.67). The value of Cohen’s d indicated a small effect size.

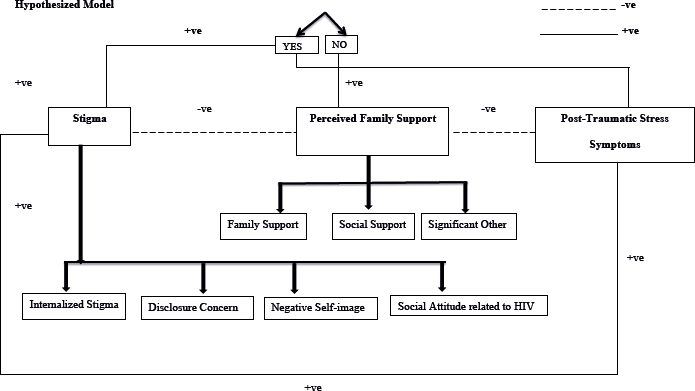

According to the hypothesized model (Figure 2) of the current study, stigma has a positive relationship with the development of PTSS, negative relationship between experiencing stigma and perception of family support, and negative relationship between PFS and development of PTSS. Table 2 shows a significant relationship between stigma, PFS, and PTSS. There is a significant strong positive relationship between stigma and internalized stigma, stigma and disclosure concern, stigma and negative self-image, and stigma and social attitude related to HIV. There is a significant weak negative relationship between stigma and PFS, stigma and family support, and stigma and social support. There is a significant positive association between stigma and PTSS.

Figure 1. Bar chart showing source of transmission of HIV in n = 100 patients.

Table 1. Relationship between disclosure about illness and stigma and perceived family support (n = 100).

| YES (47) |

NO (53) |

95% CI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | M | SD | M | SD | t(98) | p | LL | UL |

| S | 124.42 | 18.69 | 108.43 | 21.4 | -3.98 | 0.001*** | -23.94 | -8.03 |

| IS | 51.4 | 10.56 | 44.4 | 10.95 | -3.24 | 0.001*** | -11.26 | -2.71 |

| DC | 28.06 | 3.36 | 24.7 | 3.95 | -4.58 | 0.001*** | -4.8 | -1.9 |

| NS | 38.43 | 5.52 | 34.7 | 6.07 | -3.21 | 0.001*** | -6.03 | -1.4 |

| SA | 61.68 | 9.78 | 54.6 | 10.73 | -3.42 | 0.001*** | -11.09 | -2.94 |

| PFS | 3.77 | 1.67 | 4.42 | 1.46 | -2.04 | 0.04* | -1.26 | -0.01 |

| FS | 4.06 | 2.02 | 4.78 | 1.77 | -1.89 | 0.05* | -1.47 | 0.35 |

| SO | 3.51 | 1.86 | 4.26 | 2.01 | -1.93 | 0.05* | -1.5 | 0.01 |

DC = Disclosure concern, FS = Family support, IS = Internalize stigma, NS = Negative self-image, PFS = Perceived family support, S = Stigma, SA = Social attitude related to HIV, SO = Significant other. Note. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

There is a significant weak negative relationship between the perception of family support and internalized stigma, PFS and negative self-image, PFS and social attitude related to HIV, and PFS and PTSS. There is a significant strong positive association between PFS and family support and PFS and social support.

There is a significant moderate positive relationship between post-traumatic stress and internalized stigma, PTSS and disclosure concern, PTSS and negative self-image, and PTSS and social attitude related to HIV. There is significant weak negative relationship between PTSS and family support.

Discussion

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first of its kind in Pakistan to investigate the relationship between stigma, PFS, and PTSS experienced by HIV-positive patients. It further explored the differences in experiencing stigma and PFS in people who had disclosed their illness. Moreover, various demographic characteristics were probed to identify the key etiological factors involved in the transmission of HIV in patients reporting from different cities of Pakistan.

Demographic analysis of the present study shows that majority of the participants were male and only a few transgenders were included. Majority of the participants did not disclose their illness to their families due to fear of stigma and discrimination, whereas less than half disclosed about their illness to their families to call for care and support and to overcome the stress and anxiety inflicted by the disease. According to a recent (2019) report of the International daily newspaper, “THE NEWS,” 75,000 patients were reported in Punjab, 60,000 in Sindh, 5,000 in Balochistan, and 15,000 in KPK24. This increase in HIV spread is attributed to drug abuse with injection, use of contaminated needles, blades, dental tools, contaminated blood transfusion, contraction from husband or sexual partner through unsafe sex, lack of knowledge, and awareness and religious considerations in lower to middle-income families regarding the use of contraceptives in Pakistan.25

Figure 2. Hypothesized model.

Table 2. Summary of intercorrelation between subscales of stigma, perceived family support, and post-traumatic stress symptoms among HIV-positive patients (n = 100).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. S | 1 | 0.938** | 0.796** | 0.935** | 0.972** | -0.299** | -0.217* | -0.279** | -0.219* | 0.633** |

| 2. IS | 1 | 0.655** | 0.831** | 0.951** | -0.351** | -0.255* | -0.318** | -0.267** | 0.615** | |

| 3. DC | 1 | 0.755** | 0.736** | -0.166 | -0.080 | -0.161 | -0.155 | 0.508** | ||

| 4. NS | 1 | 0.894** | -0.306** | -0.228* | -0.285** | -0.219* | 0.543** | |||

| 5. SA | 1 | -0.295** | -0.232* | -0.280** | -0.195 | 0.610** | ||||

| 6. PFS | 1 | 0.766** | 0.805** | 0.828** | -0.239* | |||||

| 7. FS | 1 | 0.390** | 0.472** | -0.231* | ||||||

| 8. SS | 1 | 0.518** | -0.173 | |||||||

| 9. SO | 1 | -0.172 | ||||||||

| 10. PTS | 1 | |||||||||

| M | 116.9 | 48.11 | 26.48 | 36.68 | 58.38 | 4.11 | 4.44 | 4 | 3.91 | 38.64 |

| SD | 21.46 | 11.25 | 4 | 6.05 | 10.77 | 1.59 | 1.92 | 2.07 | 1.97 | 21.45 |

DC = Disclosure concern, FS = Family support, IS = Internalize stigma, NS = Negative self-image, PFS = Perceived family support,

PTS = Posttraumatic stress, S = Stigma, SA=Social attitude related to HIV, SO = Significant other, SS = Social stigma. Note. *p < 0.05,

**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Limited researchers have identified HIV disclosure issues, including how HIV-related stress and stigma get affected by disclosure and how it impacts the support and care of HIV patients. Research carried out in Ghana identified that PLWH who had a higher perceived stigma and emotional stress encountered greater concerns related to HIV disclosure.26 Another study revealed that the apprehensions of disclosure positively correlated with the HIV-associated stigma. These concerns were found to be higher in females and unmarried patients in comparison to other PLWH.27 Furthermore, this life-threatening condition is traumatic for the patient and they experience intrusive thoughts about illness and death. In these scenarios, depression and PTSD emerge as the most frequently occurring phenomena requiring urgent medical and psychological care.28

The present study revealed that people who had disclosed illness experienced more stigmatization as compared to those who did not. According to the American Medical Association29, HIV-positive patients who do not disclose illness experience isolation and stress while detaching themselves from society to maintain secrecy. Clark et al.30 suggested that people were afraid of discrimination and stigma due to which they preferred not to disclose. Negative self-image and internalized stigma also worsen the illness and make HIV-positive patients more prone to PTSS. Howell and Maguire31 also reported a significant relationship between stigma and disclosure.

The current study reports a significant mean difference in the level of family support after disclosure of disease as compared to nondisclosure. It is also evident in the literature that when a person discloses their seropositivity, the perception of available support decreases eventually, due to the increase in stigma related to HIV seropositivity. Huang et al.32 report that family support is very important during the first 2 years of diagnosis as the patients is undergoing lot of stress and uncertainty regarding his/her health. However, many patients have fear of family rejection and discrimination leading to nondisclosure or more isolation after disclosure.

Stigma has a significant strong positive relationship with PTSS. Breet et al.33 studied PTSD in HIV-positive patients after experiencing stigma in Nigeria. They reported that AIDS is a lifelong successive illness; during treatment, the person experiences a series of traumas thus leading to psychological issues. HIV seropositivity serves as a trigger for developing PTSS because stigma is severe enough to introduce death threat, shame, loss of loved ones, and integrity. All these stigmatizing events play an important role in intensifying fear, helplessness, and feeling of loss. The people who are experiencing PTSD symptoms consistently re-experience stigmatizing occasions.34

Furthermore, the current study showed that post-traumatic stress has significant weak negative relationship with family support. An increase in perception of family support has likelihood to cause a decrease in PTSS. Clinical evidence reveals that PTSD is linked with disease progression of HIV which is characterized by a significant decline in CD4+ cells.35 When a person has a less stressful life with the support of family members, their immune system starts working in a responsive manner with consequent better quality of life and lesser chances of rapid progression of the disease.

Conclusion

A considerable level of stigma is experienced by HIV-positive patients, which is associated with gender, level of family support, and stress disorders. A decrease in the perception of family support is associated with the disclosure of the disease and thus the development of PSTD in these patients. Therefore, sufficient family support can act as an excellent buffer against the stigma and help in reducing psychological distress.

Limitations of the study

The study is to be reviewed considering the following limitations encountered while conducting the research. The sample of the study is not representative of the population as it comprised only those patients who were attending the healthcare facilities. This makes the study less generalizable concerning social diversity. Many patients were uncomfortable sharing their intrinsic experiences of living with HIV and refused to respond to the questions appropriately. Lastly, sufficient amount of privacy could not be warranted due to unfavorable logistic arrangements, such as lack of space for the administration of questionnaires which might have led to respondents’ bias.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the Punjab AIDS Control Program (PACP) Primary and Secondary Healthcare Department, the Government of Punjab, and the Khawaja Sira Society for their logistic and clinical support for the recruitment of patients and acquisition of relevant data.

List of Abbreviations

| AIDS | Acquire immunodeficiency syndrome |

| DG Khan | Dera Ghazi Khan |

| DSM–5 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition |

| HSS | HIV stigma scale |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| KPK | Khyber Pakhtunkwah |

| MPSS | Multidimensional scale of perceived social support |

| NGOs | Nongovernmental organizations |

| PACP | Punjab AIDS control program |

| PCL-5 | Post-traumatic stress disorder checklist |

| PFS | Perceived family support |

| PLWH | People living with HIV |

| PTSD | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

| PTSS | Post-traumatic stress symptoms |

Conflict of interest

None to declare.

Grant support and financial disclosure

None to disclose.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Bioethics Committee of Government College University, Lahore, Pakistan, vide Letter No. GCU/IIB/639 dated 1-11-2021.

Authors’ contributions

KZ: Conception and design of the study, acquisition and analysis of data, and drafting of the manuscript with critical intellectual input.

FK: Analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript with critical intellectual input.

ALL AUTHORS: Approval of the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Authors’ Details

Kiran Zia1,2, Faiza Khalid1,3

- Former Student, MS Clinical Psychology, Government College University, Lahore, Pakistan

- Lecturer, Department of Eastern Medicine, Qarshi University, Lahore, Pakistan

- Lecturer, Department of Humanities & Social Sciences, University of Gujranwala Institute of Future Technology, Gujranwala, Pakistan

References

- Akhlaq JI, Rana H, Ashraf R. Perceived stigma and mental health: mediating role of coping strategies in people living with HIV positive. Pak J Prof Psy: Res Prac. 2021 [cited 2022 Jul 3];12(2):32–43. Available from: http://pu.edu.pk/images/journal/clinicalpsychology/PDF/3_v12_2_21.pdf.

- Carlsson G. UNAIDS data 2019. UNAIDS. 2019 [cited 2022 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2019-UNAIDS-data_en.pdf.

- National AIDS Control Program. PNACP data 2019. NACP. 2019 [cited 2022 Jul 3]. Available from: http://www.nacp.gov.pk/index.html.

- Ahmed A, Hashmi FK, Khan GM. HIV outbreaks in Pakistan. Correspondence. 2019;6(7):418. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30179-1

- Pokrovskiĭ VV, Iurin OG, Kravchenko AV, Potekaev NS, Gabrilovich DI, Makarova NL, et al. Pervyĭ sluchaĭ VICh-infektsii u grazhdanina SSSR [The first case of HIV infection in a citizen of the USSR]. J Microbiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 1992;11:19–22.

- United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. UNAIDS data 2021. UNAIDS. 2021 [cited 2022 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC3032_AIDS_Data_book_2021_En.pdf.

- Sweeney SM, Vanable PA. The association of HIV-related stigma to HIV medication adherence: a systematic review and synthesis of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(1):29–50. https://doi.org/doi:10.1007/s10461-015-1164-1.

- Kapila A, Chaudhary S, Sharma RB, Vashist H, Sisodia SS, Gupta A. A review on HIV/AIDS. Ind J Pharm Biol Res. 2016;4(3):69–73. https://doi.org/doi:10.30750/ijpbr.4.3.9

- Ginossar T, Oetzel J. It’s a dark cloud: experiences of social undermining among people living with HIV in New Mexico. J Appl Commun Res. 2019;47(2):175–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2019.1583358

- Saki M, Kermanshahi SMK, Mohammadi E, Mohraz, M. Perception of patients with HIV/AIDS from stigma and discrimination. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2015;17(6). https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.23638v2

- Subu MA, Wati DF, Netrida N, Priscilla V, Dias JM, Abraham MS, et al. Types of stigma experienced by patients with mental illness and mental health nurses in Indonesia: a qualitative content analysis. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2021;15(77). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-021-00502-x

- Heggeness LF, Brandt CP, Paulus DJ, Lemaire C, Zvolensky MJ. Stigma and disease disclosure among HIV+ individuals: the moderating role of emotion dysregulation. AIDS Care. 2017;29(2):168–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2016.1204419.

- Stephen MH, Perazzo JD, Ruffner AH, Lyons MS. Exploring current stereotypes and norms impacting sexual partner HIV-status communication. Health Commun. 2020;35(11):1376–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2019.1636340.

- Dejman M, Ardakani HM, Malekafzali B, Moradi G, Gouya MM, Shushtari ZJ, et al. Psychological, social, and familial problems of people living with HIV/AIDS in Iran: a qualitative study. Int J Prev Med. 2015;6:126. https://doi.org/10.4103/2008-7802.172540.

- Catona D, Greene K, Magsamen CK. Disclosure message choices: an analysis of strategies for disclosing HIV+ status. J Health Commun. 2015;20(11):1294–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1018640.

- Zhang C, Li X, Yu L, Qiao S, Zhang L, Zhou Y, et al. Emotional, physical and financial burdens of stigma against people living with HIV/AIDS in China. AIDS Care. 2016;28(1):124–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2016.1146206.

- Boyes ME, Cluver LD. Relationships between familial HIV/AIDS and symptoms of anxiety and depression: the mediating effect of bullying victimization in a prospective sample of South African children and adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44(4):847–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0146-3.

- Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC, Littlewood RA. Impact of HIV-related stigma on health behaviors and psychological adjustment among HIV-positive men and women. AIDS Behav. 2016;10(5):473–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-006-9099-1

- Akhtar O, Qazi O, Yasmin H, Bano K, Qamar S. Frequency of HIV among patients seeking antenatal care at a tertiary care hospital, Karachi. J Pak Med Assoc. 2022;72:855–9. https://doi.org/10.47391/JPMA.1816.

- Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(6):518–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.10011.

- Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S. Berkoff KA. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1990;55:610. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005109522457.

- Jibeen T, Khalid R. Predictors of psychological well-being of Pakistani immigrants in Toronto, Canada. Int J Intercult Relat. 2010;34(5):452–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.04.010.

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, Schnurr PP. The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Nat Cent PTSD. 2013 [cited 2022 Jul 3]. Available from: www.ptsd.va.gov.

- Uncontrollable AIDS/HIV in Pakistan - its alarming growth - misuse of global AIDs funding. News. 2019 [cited 2022 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/491519-uncontrollable-aids-hiv-in-pakistan-its-alarming-growth-misuse-of-global-aids-funding.

- Hasnain SF, Johansson E, Gulzar S, Krantz G. global need for multilevel strategies and enhanced acceptance of contraceptive use in order to combat the spread of HIV/AIDS in a Muslim society: a qualitative study of young adults in urban Karachi, Pakistan. J Health Sci. 2013;5(5):57–66. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v5n5p57.

- Anakwa NO, Teye-Kwadjo E, Kretchy IA. Effect of HIV-related stigma and HIV-related stress on HIV disclosure concerns: a study of HIV-positive persons on antiretroviral therapy at two urban hospitals in Ghana. App Res Qual Life. 2021;16:1249–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-020-09813-6.

- Hussain MM, Khalily MT, Zulfiqar Z. Psychological problems among patients suffer in HIV/AIDS in Pakistan. Rev App Manag Social Sci. 2021;4(2):559–67. https://doi.org/10.47067/ramss.v4i2.156.

- Tang C, Goldsamt L, Meng J, Xiao X, Zhang L, Williams AB, et al. Global estimate of the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among adults living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;10(4):032435. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032435.

- Promoting inclusive gender, sex, and sexual orientation options on medical documentation. Am Med Assoc. 2016 [cited 2022 July 3]. Available from: https://assets.ama-assn.org/sub/meeting/documents/i16-resolution-212.pdf.

- Clark HJ, Lindner G, Armistead L, Austin BJ. Stigma, disclosure, and psychological functioning among HIV-infected and non-infected African-American women. Women Health. 2014;38(4):57–71. https://doi.org/10.1300/j013v38n04_04.

- Howell D, Maguire R. Factors associated with experiences of gender-affirming health care: a systematic review. Trans Health. 2021;13. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2021.0033.

- Huang F, Chen WT, Shiu C, Sun W, Candelario J, Luu BV. Experiences and needs of family support for HIV-infected Asian Americans: a qualitative dyadic analysis. Appl Nurs Res. 2021;58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2021.151395.

- Breet E, Kagee A, Seedat S. HIV-related stigma and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression in HIV-infected individuals: does social support play a mediating or moderating role? AIDS Care. 2014;26:947–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2014.901486.

- Breezing C, Ferrara M, Freudenreich O. The syndemic illness of HIV and trauma: implications for a trauma-informed model of care. Psychosomatics. 2015;56:107–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2014.10.006.

- Ebrahimzadeh Z, Goodarzi MA, Joulaei H. Predicting the antiretroviral medication adherence and CD4 measure in patients with HIV/AIDS based on the post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. Iran J Public Health. 2019;48(1):139. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6401591/.

Keywords: Seropositive, Stigma, Perceived family support, Post-traumatic stress

Publication History

Received: June 23, 2022

Revised: August 22, 2022

Accepted: September 06, 2022

Published: September 25, 2022

Authors

Kiran Zia

Former Student, MS Clinical Psychology, Government College University, Lahore, Pakistan

Faiza Khalid

Former Student, MS Clinical Psychology, Government College University, Lahore, Pakistan