Commentary

Volume: 40 | Issue: 3 | Published: Sep 25, 2024 | Pages: 115 - 118 | DOI: 10.24911/BioMedica/5-732

Fostering excellence: creating a positive clinical learning environment for medical students

Authors: Khalid Rahim Khan , Ambreen Khalid

Article Info

Authors

Khalid Rahim Khan

Director Medical Education and International Linkages, University of Health Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan.

Ambreen Khalid

Associate Professor of Physiology, Pakistan

Publication History

Received: August 15, 2024

Accepted: September 18, 2024

Published: September 25, 2024

Abstract

NOT APPLICABLE

Keywords: Excellence, Medical Education, Learning Environment, Medical students

Biomedica - Official Journal of University of Health Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan

Volume 40(3):115-118

COMMENTARY

Fostering excellence: creating a positive clinical learning environment for medical students

Khalid Rahim Khan1*, Ambreen Khalid2

Received: 15 August 2024 Revised date: 02 September 2024 Accepted: 18 September 2024

Correspondence to: Khalid Rahim Khan

*Director Medical Education and International Linkages, University of Health Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan.

Email: khalidrahimdme@uhs.edu.pk

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

Medical education is a constantly evolving paradigm. The dynamic upgrading and innovative approach to medical education is always grounded in the core concepts of patient care and scientific basis.1 The relation of any educational practice, teaching methodology, and experiential process with the central tenet of patient care remains integral. Thus, the evolution of any upgrade, evolution, or innovation of our teaching embodies the necessary context, aligning our learners’ needs with our professional practice as we implement them in our classrooms and bedside learning environment.2

Medical curricula in the current era are getting more specific in competency acquisitions and outcome base. The skill-based competency acquisition in a clinical environment with early-on clinical orientation is the spiral of psychomotor learning which is cultivating a yield of doctors who are more apt on applied requirements they are looked up to Foshee et al.3. With this backdrop, the faculty and healthcare leaders now need a more categorial effort to develop a conducive clinical culture for undergraduate student training. The optimization of clinical practices in a clinical unit for all tiers of training and practice best models a learning environment for an undergraduate student to walk in Foshee et al.3.

Most of the medical colleges across Punjab have now adopted an integrated curriculum. The paradigm of curriculum integration itself prepares the learner for a more convenient transition to the clinical years. However, institutions and clinical departments are suggested to make the learning experiences during these years more conducive, hands-on, and with a synergistic approach to developing sound affective traits for promising professionals.4

Undergraduate medical education aims to deliver a comprehensive understanding of the set of professional, clinical, and behavioral expectations. Students are expected to be professional in their conduct. The entire clinical faculty serves as the role model for the students. Existing professional practices in a clinical unit would serve as the declared institutional standards. So, a deliberate and categorial workup regarding setting a conducive environment of clinical learning backed by meticulous clinical behaviors must be undertaken by all professionals, of all tiers, always.5

Developing a robust clinical culture needs an institutional ideology that all tiers must declare, endorse, adopt, and implement. A mechanism must be devised to commit to these details.1

A substantive clinical culture would nurture, support, and challenge students to become skilled, compassionate, and ethical healthcare professionals with uncompromised patient safety and care. A clinical culture is rooted in committed values, professional behaviors, and clinical approaches based on patient-centric care.6

The core significance as we draft our specifics, operating procedures, protocols, and guidelines at the unit/institutional level, remains patient care and safety. Patient safety entails a prospective planning by the leader to have an ironclad robust system to anticipate patient vulnerabilities before their occurrence. However, the diversity of factors may not limit the patient safety event to an absolute zero. Our students should step into a learning environment that has an explicit mechanism of observing, recording, analyzing, and future planning for any patient safety-related occurrence. To ensure that learners of all tiers, under and postgraduate, for all domains, learners should see protocols in practice and implemented in true spirit as they go through their clinical rotations.7

The quality of healthcare offered at a clinical unit should also have open channels of feedback from all tiers of learners. It should also incorporate quality enhancement suggestions from all facets of interprofessional teams working in the clinical unit. Thus, the sense of responsibility trickles down to the learners’ and the leader shares the onus of the clinical learning environment. Specifically, the postgraduate students should engage in defining, implementing, and ensuring the healthcare quality standards in the respective clinical settings. In a non-threatening environment, the culture of reciprocating feedback is essentially an enhancing factor.2

Creating a clinical learning environment is the true calling of a clinical healthcare leader. It is pertinent to account for all the learners’ needs. The collective learners’ needs could be identified by the curriculum or global evidence. However, clinical units and institutions should be more objective when identifying individual learning needs. The flexibility of training for individual skill acquisition may be incorporated only if experiential learning is considered for learners at an individual level. Competency acquisition mapping to be done at the institutional level and implemented at the clinical unit level will help identify the individual learning needs of the students.8

As a clinical healthcare leader as we draft our protocols and guidelines, one significant consideration for the well-being of the patients is the consideration of stresses and detriments for the healthcare giver. A conducive learning environment should ensure that the learners and all the members of interprofessional teams should be optimally active and determined. A special awareness for detecting and curtailing burnout among the residents and students should be inculcated in the peers and senior faculty. Deliberated protocols for detecting burnout and flexible options should be a part of the institutional protocols.2

An important component of developing a sound clinical learning environment is to develop interprofessional educational practices in clinical settings. Interprofessional education improves team building, and sense of responsibility and ensures immaculate patient care transitions.2

An overarching approach to creating a conducive clinical learning environment needs a strong underpinning of standardized clinical supervision. All the protocols of patient safety, healthcare quality, interprofessional team building, experiential clinical learning, healthcare worker well-being, and developing a sense of patient ownership require a well-calibrated explicitly detailed supervisory standard.9 These supervisory standards provide the essence of learning for undergraduate medical students in the clinical rotations. These standards should ensure that all the faculty practices, procedural protocols, and communication standards are carried out following the international standards of medical ethics and professionalism. Institutional training of all clinical supervisors should be standardized and documented. Faculty training should be a well-incorporated feature in the annual action plan. A clearly defined supervisory role for progressive levels of students’ autonomy through the undergraduate and postgraduate learning years is the hallmark of excellence.9

The most important aspect of developing a conducive clinical learning environment is the culture of mutual respect for the students, learners, patients, and faculty. A culture fostered through mutual respect, harbors the best cognitive development and interprofessional collaboration. Educational curiosity is not to be curbed, to strengthen the critical thinking and competency acquisition of our learners. This can primarily be done through a learning environment of respect and expression.10

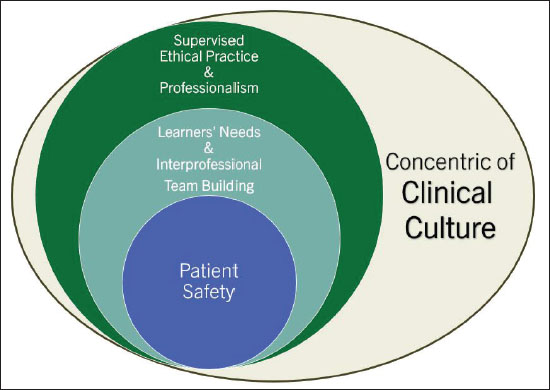

A model “Concentric of Clinical Culture” (Figure 1) is proposed to ensure all the elements described in this editorial. This model depicts the hierarchy of the core concept of patient and builds up to the overarching practice of supervision of clinical standards, culture of respect, ethical norms, professional practices, sense of ownership, and reciprocity of feedback.

All institutes and clinical units should deliberate upon the essentials of setting the clinical learning environment for their students to step in. The institutional core values will be evident only if carefully deliberated upon and implemented.

A few tips for developing a conducive clinical learning environment are as follows:

Establishing a nonpunitive learning environment where interprofessional students, faculty, and healthcare professionals respect mutual roles and responsibilities.

- Ownership of the clinical faculty for creating clinical educational experiences for the learners, for their competency acquisitions in supervised clinical activities that match their level of competence.

- Incorporating and ensuring evidence-based protocols are implemented in the respective clinical settings.

- Creating a psychologically and physically safe learning environment with liberty for educational relevant expression and inquisitiveness.

- Designing clinical teaching opportunities that focus on patient needs, preferences, and values, relevant to the community context.

- Developing a two-way feedback mechanism as a norm for learning as well as healthcare quality improvement.

- Implement standards for supervision, faculty development, and relevant clinical training needs.2

The clinical learning environment and educational culture ingrain the core professional values, in a yield of professionals. Thus, a resounding effort to thoroughly develop and implement all facets of a conducive clinical learning environment.

Figure 1. Concentric of clinical culture.

List of abbreviations

None.

Conflict of interest

None to declare.

Grant support and financial disclosure

None to disclose.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Author’s contributions

KRK, AK: Main concept and design of the study, acquisition, and analysis of data, drafting of manuscript, critical intellectual input, approval, and responsibility for the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Authors’ Details

Khalid Rahim Khan1, Ambreen Khalid2

- Director Medical Education and International Linkages, University of Health Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan

- Associate Professor of Physiology, Pakistan

References

- Tokuç B, Varol G. Medical education in the era of advancing technology. Balkan Med J. 2023;40(6):395. https://doi.org/10.4274/balkanmedj.galenos.2023.2023-7-79

- Co JPT, Weiss KB; CLER Evaluation Committee. CLER pathways to excellence, Version 2.0: executive summary. J Grad Med Educ. 2019 Dec;11(6):739–41. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-19-00724.1

- Foshee CM, Walsh H, Van der Kloot TE, Boscardin CK, Calongne L, Telhiard NS, et al. Pursuing excellence: innovations in designing an interprofessional clinical learning environment. J Grad Med Educ. 2022 Feb;14(1):125–30. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-21-01177.1

- Wajid G, Baig L, Ali SK, Mahboob U, Sethi A, Khan RA. The role of Pakistan Medical & Dental Council in steering undergraduate medical curriculum reforms in Pakistan. Khyber Med Univ J. 2024;16(4):201–6. https://doi.org/10.35845/kmuj.2024.23822

- Mohammadi E, Shahsavari H, Mirzazadeh A, Sohrabpour AA, Mortaz Hejri S. Improving role modeling in clinical teachers: a narrative literature review. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2020 Jan;8(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.30476/jamp.2019.74929

- Tye J, Dent B. Building a culture of ownership in healthcare: the invisible architecture of core values, attitude, and self-empowerment. Sigma Theta Tau. 2024 Feb 21. Available from: https://apn.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=3154§ionid=264996884

- Buja A, Damiani G, Manfredi M, Zampieri C, Dentuti E, Grotto G, et al. Governance for patient safety: a framework of strategy domains for risk management. J Patient Saf. 2022 Jun 1;18(4):e769–800. https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0000000000000947

- Hawkins RE, Welcher CM, Holmboe ES, Kirk LM, Norcini JJ, Simons KB, et al. Implementation of competency‐based medical education: are we addressing the concerns and challenges? Med Educ. 2015 Nov;49(11):1086–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12831

- Al-Eraky MM. Twelve tips for teaching medical professionalism at all levels of medical education. Med Teach. 2015;37(11):1018–25. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2015.1020288

- Jain S, Dewey RS. The role of “Special Clinics” in imparting clinical skills: medical education for competence and sophistication. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2021;20(2):513–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S306214